The Vagelos programs have a reputation at Penn.

They’re hard or cutthroat or prestigious or give students great research experience.

“This is the kind of thing that people will say after five or six years, ‘Well, that was a good thing to have done.’ Past tense,” said Ponzy Lu , chemistry professor and the director of the Vagelos Molecular Life Sciences program.

“I think most of them say it in the present tense, but I’m not sure if they’re being honest,” he added. “If they say it’s fun to do, then we’re not working them hard enough.”

There frequently seems to be a joke lingering around Lu’s comments, but it’s never quite clear how much he means seriously.

That kind of uncertainty about the true nature of the Vagelos programs may be part of another common stereotype — that students often start but seldom finish the programs.

“The program does have a notorious drop rate,” said College junior Josh Bryer , who was in MLS until halfway through his freshman year. The Molecular Life Sciences program focuses on chemistry and biochemistry within the College, with the vast majority of students opting to submatriculate for a master’s degree in four years.

Placed next to the image of the Vagelos programs as models of Penn’s interdisciplinary approach, an interesting juxtaposition arises.

Retention numbers are one way to look at student satisfaction with each of the three programs established through donations by 1950 College graduate Roy Vagelos and his wife Diana. The statistics aren’t the same across the board. Just as the three programs have extremely different academic focuses, they also have varying retention rates.

But, as usual, the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

With a retention rate of 100 percent, the Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research would appear to have the highest customer satisfaction. Out of the 10 sophomores and 15 freshmen in VIPER, none have switched out, VIPER Faculty Co-Director Andrew Rappe said.

But since the program is only two years old, managing director Kristen Hughes said that retention is “a tough question to answer right now.”

The Life Sciences and Management Program, a joint degree program between the College and Wharton that focuses on the intersection of business and bioscience, has both a small starting pool and a low dropout rate.

Since the start of the program in 2006, 28 of 209 students have dropped out, including some who have not yet graduated, for a drop rate of about 13 percent, according to Director of Administration and Advising for LSM Peter Stokes .

LSM Faculty Co-Director Philip Rea said that out of a class of 25 students, two or three students generally decide to leave the program.

“I would say the dropout rate for LSM is relatively low,” he said.

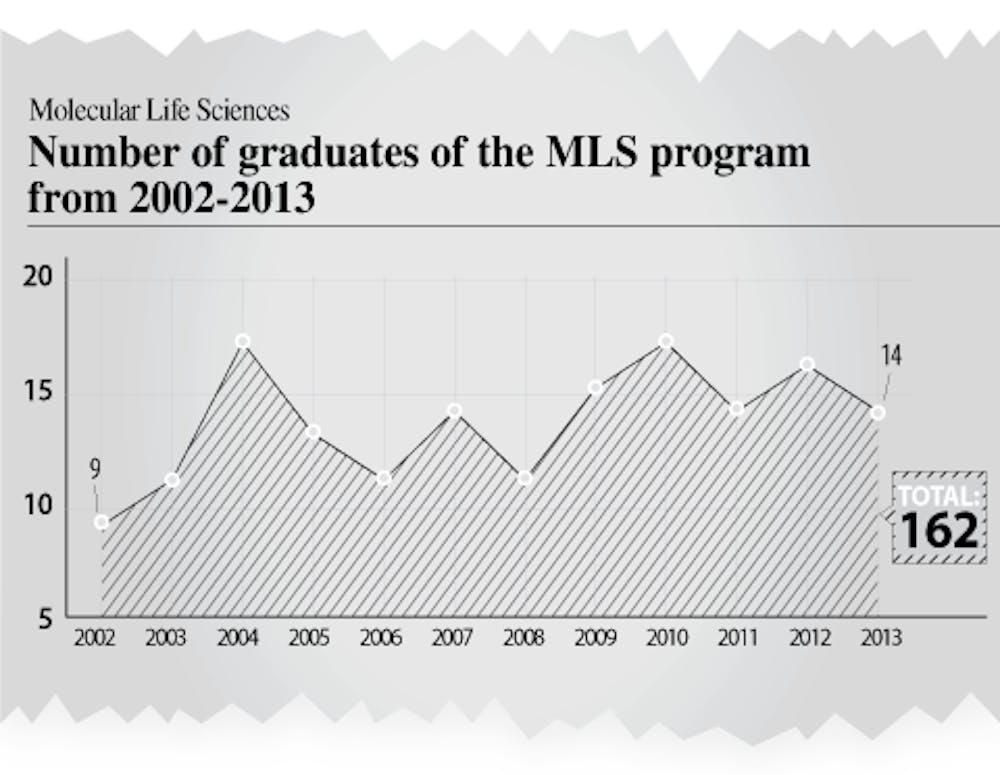

Apart from being the oldest of the Vagelos programs, MLS is also the largest and the one with the lowest retention rate. From 2002 to 2013, 162 students graduated from MLS, which is an average of 13.5 per year out of a typical freshman class of between 50 and 60 students — about a 77 percent drop rate.

Lu said that over the past three years, about 15 of the 50 to 60 students have typically graduated. This year, 14 will complete the program, and in future years he expects the numbers to be closer to 20.

In general, though, the leaders of the Vagelos programs don’t see retention rates as being reflective of the programs’ success.

For Lu, MLS is an opportunity for students to see if scientific research is the right field for them.

“The problem [with focusing on retention] I see is that, of the people who start, a large fraction of them really didn’t want this, but we give them a chance to see if they like it,” Lu said.

Incoming freshmen may request an interview at the time of their acceptance to discuss admission to the MLS program, and anyone who indicates an interest in chemistry or biochemistry on their application is automatically considered for the program. For the other two Vagelos programs, on the other hand, students must explicitly apply to be considered.

Most of the students interviewed said they were offered acceptance into MLS along with their admission to Penn. Many were focused on science in high school, so acceptance into a specialized and prestigious science program seemed like a perfect opportunity. They decided to give the program a try.

College junior Peter Yin , who was in MLS for a year and a half, said that the non-traditional style of joining the program might impact its retention numbers.

“I think it’s easier to drop MLS because you didn’t apply for it,” he said.

While the retention statistics themselves are telling in some regards, they don’t necessarily show the truth behind the numbers. The reputation that the Vagelos programs foster extreme competitiveness and aim to weed out those who can’t keep up doesn’t match up with many students’ experiences in the programs.

While the retention rate isn’t high in MLS, often the choice to leave the program is due to a shift in academic interest rather than an inability to keep up with the courses.

“A very small percentage just don’t do so well, but that probably would’ve happened with anything,” Lu said.

The same is true for LSM.

“Some people do drop out, but it’s almost always their choice and it has to do with their priorities and their interests changing over their time in college,” Stokes said.

College and Engineering sophomore David Lim, who is currently in the VIPER program, said that although he and his friends have discussed the challenges of the demanding coursework of the program, none of them have considered quitting VIPER.

There was a time when he considered pursuing a pre-med track instead of VIPER, but ultimately, he said, “I realized that I have too strong of an interest in basic science to be a pre-med.”

Rea said that if LSM students decide to go in a different direction, the most common choice is to pursue a single degree within Wharton.

“I think that it’s partly because they can see the sort of obvious use that they’re going to be able to use of their Wharton education, whereas to a few of them, it’s a bit less clear what they’ll do with their science education,” Stokes said.

“The other factor is that at this point in time, LSM is housed in the Wharton building,” Rea added, which he said will change in 2016 when the program moves from Steinberg-Dietrich Hall to its own space in the Neural and Behavioral Science building.

He said that other students opt for a science degree in the College, usually choosing to study biology, biochemistry or biological basis of behavior.

Engineering and Wharton junior Ashwin Baweja said the entrepreneurial aspect of the program was attractive as he was applying to Penn, but he decided after the first semester of his sophomore year in LSM that a different academic track was a better fit for him.

“For me, it was more of my interests changing throughout college,” he said.

For many students originally in the MLS program, their academic interests diverged over time from the focus of the program.

When she took her first philosophy class at Penn, College junior Sara Chodosh realized that her academic interests were broader than pure hard science, so she switched her double major to neurobiology and philosophy and science outside of MLS.

For students who want to take a wider range of classes or aren’t entirely committed to the research component, MLS often isn’t the right fit.

The MLS freshman seminar requires students to read science-related articles from the past week to keep abreast of emerging scientific research and trends. But that emphasis on the research component showed College sophomore Kevin Pan that his academic interests lie elsewhere.

“It’s the perfect program for someone who is dedicated to having a career or at least researching the physical sciences,” said College sophomore Aziz Kamoun, a former MLS student and an economics and history double major. “Otherwise, I think that if it’s a program that you do half-heartedly, I think there’s a risk of not making the best use of your time.”

Other MLS course requirements are often indicators that the program isn’t the right choice. But it’s the content, not the academic rigor, that often drives that decision. The focus of the high-level theoretical physics and chemistry classes isn’t always appealing, pointing students in another direction.

Lu and Stokes described their programs as being intended to find the students who are truly committed rather than actively trying to weed out the others. “We’re not interested in retention, we’re interested in finding people who want to do this stuff,” Lu said. “So we’re actually looking for people, we’re not trying to screen people out.”

Chodosh, who left MLS after her freshman year, disagreed with that assessment of the program, saying that she felt that Lu “took pride in being able to weed people out.”

But for the rest of the students, Lu’s description of the program’s approach was fair.

“Is there somewhat of a sense of, ‘If you’re not doing well, you should probably leave?’” College junior Sarah Murray, who was in MLS, said. “Yeah, but generally it’s the people who stay in it that are the ones who want to be in it.”

Many praised Lu’s supportiveness when they informed him of their decisions to leave the program, and Bryer said he was particularly helpful in putting him in contact with another faculty member for his new classics major.

But for some students, the decision to leave the Vagelos program wasn’t just academic.

“There’s a very competitive nature to the program and, at least for me, that made it hard for me to feel like I fit in,” Chodosh said of MLS.

Chodosh said the program lacked a sense of community, one of the driving forces behind her decision to leave MLS.

That’s not the case for all students, however.

“There was definitely a little bit of a sense of competitive nature around people, but there are also groups of people in Vagelos who are more laid back and more friendly,” said Yin, the junior who was in MLS until midway through his sophomore year. “So it’s not like everyone’s cutthroat.” Murray, too, found a community of “immediate friends” within MLS.

Baweja, who left the LSM program, said that it fostered a great sense of community and that people tended to be very friendly, especially compared to his experiences with other students in Wharton and Engineering. “[LSM students] were some of the first students I met at Penn and they’re some of my best friends today,” he said.

Still, there seemed to be a looming feeling that not everybody in the MLS program would stay all four years, said 2013 College graduate Jake Robins, who switched out of MLS in his sophomore year.

He said that as a form of “quiet intimidation,” Lu would joke that there was only enough funding for 15 students to complete the program.

But Pan, who left MLS in the beginning of his sophomore year, said he thinks that having few graduates each year is an inherent part of the program and is not necessarily a flaw. “I think part of the program is to have really strong graduates of the program, and it makes sense that only the best students actually make it through,” he said.

Some students view staying in the program as a source of pride, given its rigor and intensity.

“I found the most difficult part of dropping out of the program was my ego,” Yin said. He said that he had to remind himself that his decision was based on a different academic interest, not an inability to keep up with the work.

“Getting over that mental hump is the hardest part,” he said.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.