In 2012, a psychiatrist at Penn’s Counseling and Psychological Services emailed the CAPS director to discuss the lengthy wait time for students to get an initial appointment.

Nick Garg, who served as a full-time CAPS psychiatrist from 2003 until 2012, was concerned about what he perceived as an increase in the time it took for students to get an appointment. But his concerns were brushed aside, Garg said. He said he tried to discuss what he viewed as problems at CAPS with CAPS Director Bill Alexander and other administrators, without success.

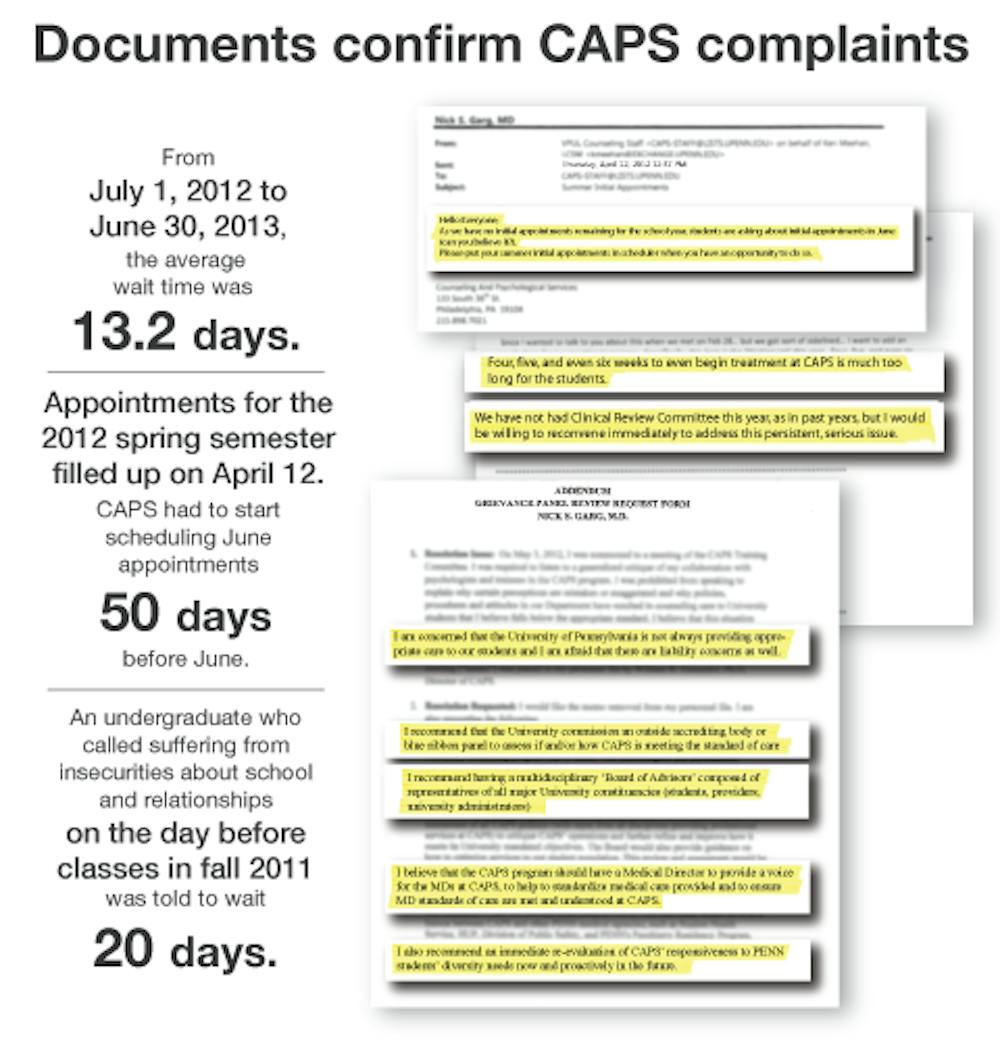

Documents provided by Garg to The Daily Pennsylvanian - including notes on cases he was involved in, emails between CAPS staffers and intake forms for students calling CAPS - give a glimpse into the inner workings of an office that has come under scrutiny this semester after two suicides just weeks apart. The documents confirm several common complaints about CAPS, including the long waits to get an appointment, and raise questions about other aspects of CAPS’ operations.

Garg was fired from CAPS in September 2012 for allegedly slapping a CAPS psychologist during a staff meeting in June of that year - an allegation he denies. He filed a complaint against Penn in the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations over his dismissal, alleging wrongful termination.

Alexander declined to comment on Garg’s specific complaints, citing the University’s policy of not commenting on ongoing litigation, but he was willing to speak generally about CAPS practices and policies.

“I disagree with [Garg’s] characterization of CAPS and its processes,” Alexander said in an emailed statement. “CAPS provides counseling and psychological services on a confidential basis to all students, on an urgent (walk-in) or appointment basis, providing immediate care to those in need. CAPS uses a collaborative treatment team approach that involves clinicians, social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and trainees, to provide the best possible experience for all students.”

Wait times and call-backs

Even before the increased attention on CAPS this semester, there were complaints of long wait times to get an appointment. A University Council committee that took a detailed look at CAPS last school year found the most often reported issue was the long time it took for students to be seen. The committee criticized the degree to which students need to advocate for themselves to get services and recommended ensuring that students receive initial visits within three days of calling CAPS.

On Feb. 28, 2014, in an interview with the DP unrelated to Garg’s complaints, Alexander said the wait during CAPS’ busiest times for someone not in a crisis can reach three to three-and-a-half weeks. From July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013, the average wait time was 13.2 days, Alexander said in a January interview also unrelated to Garg’s complaints. After CAPS announced on Feb. 6 that it would hire three new clinical staffers, the wait time dropped to two to three days, Alexander said in the February interview. He expected it to rise as the new hires’ schedules filled.

However, the notes Garg provided from initial phone calls that students make to CAPS show firsthand that some students have had to wait much longer than the 13-day average. In additional interviews the DP conducted with students regarding mental health on campus, students reported wait times ranging from several days to just over four weeks.

In late June 2012, Garg sent descriptions to his lawyer of cases in which he believed CAPS had not provided adequate care to students. He detailed the cases from his memory and his personal notes. Several of the cases involved students’ mental states worsening, he said, because they had to wait to get an appointment.

One case Garg pointed to involved an undergraduate who called CAPS in late fall 2011 with mild depressive symptoms, according to Garg’s notes. She was told she had to wait six weeks or take a referral to a therapist in Philadelphia, so she took a referral. However, she didn’t like the outside psychologist, so she called CAPS again. She was told to wait another several weeks. While she waited, she began cutting herself with a kitchen knife. She called one of her parents, asking her parent to make sure she didn’t cut herself deeper or jump out of a window. The student’s parent furiously called CAPS, demanding an appointment. The student was seen immediately.

“The issue of wait time is a real, real challenge,” Victor Schwartz, a New York University psychiatry professor, said of college counseling centers. Schwartz is the medical director of the Jed Foundation, a nonprofit aimed at promoting emotional health and preventing suicide among college students. “Most of these centers are not charging a fee - which, to some extent, limits the staffing availability and creates times during the year when things get very backed up.”

Another undergraduate, who called suffering from insecurities about school and relationships the day before classes started in 2011, was told to wait 20 days, according to Garg’s notes. A graduate student calling in 2012 reported that she wasn’t suicidal at the time, but was once “playing with a knife” and considered killing herself. She had to wait 27 days before being seen at CAPS. An undergraduate who called in late November 2011 with “really bad” anxiety was told by the psychology intern taking the call that there were no more intake appointments available for the rest of the term.

In 2012, appointments for the spring semester - which ended May 8 - filled up on April 12. “As we have no initial appointments remaining for the school year, students are asking about initial appointments in June (can you believe it?),” read an email sent by a CAPS coordinator to all CAPS staff. It was 50 days until June.

Several years ago, CAPS changed its intake system with the goal of prioritizing students with acute symptoms. Students used to have an in-person intake appointment with a therapist, while today, 15-minute interviews are conducted over the phone to assess need.

While it does have downsides, Schwartz said, CAPS’ triage system is not uncommon among college counseling services.

“Any assessment isn’t perfect,” he said. “Sometimes the situation will change, and sometimes you won’t get the gravity of the problem in a brief conversation. They’re very, very helpful approaches, but they’re not foolproof.”

CAPS revised another policy in January 2014 when it began offering extended hours several days a week to better accommodate students who couldn’t make the usual 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. business day. Garg said he tried to do that years ago.

But in March 2012, Alexander, citing potential liability concerns, told him not to schedule patients after 5 p.m., Garg said.

“I have people scheduled for 5:15pm already,” Garg said in a March 28, 2012, email to Alexander. “Would you like me to reschedule them to 5pm now? Or is it OK not to schedule after 5pm from this point on.”

Alexander responded: “I think from this point on will be ok.”

Another recurring concern that students who have used CAPS raised in interviews is the lack of a follow-up call from CAPS if students miss an appointment. Garg, too, cited this as a concern and attributed it to the self-exploration model of therapy that CAPS employs. The model is driven by the idea that patients should come up with as much of their own solutions as possible.

“The thought was, if they don’t come in, they’re not invested,” Garg said. Regardless, he added, he would call his patients back. “It breaks my heart because the student is already thinking they’re worthless.”

While not commenting on specific complaints, Alexander said self-exploration was one of several models of therapy that CAPS clinicians are trained in.

“Personal self-exploration, along with many other interventions, is part of many models of psychotherapy,” he said in an email. “All of our therapy models are well grounded in the current professional literature.”

Garg began seeing a student in 2012 who waited about a month to see a psychologist. The student, an undergraduate, was enrolled in split treatment: She saw a psychologist and a psychiatrist in separate sessions. The student’s psychologist told Garg that he was closing the student’s case “due to frequent no-shows” and hadn’t reached out to the student because it “would be inconsistent with the self-exploration model,” according to Garg’s notes.

The student, for her part, told Garg that she thought the psychologist simply didn’t care.

“When students miss appointments, the therapist can contact them as a reminder and offer another appointment,” Alexander said in the email to the DP. “However, chronic no-shows or cancellations may be indicative of a larger therapeutic issue. In those cases, the clinician has discretion in how to address this. Sometimes the best clinical intervention is to allow the student the autonomy of initiating further contact.”

Looking for a ‘systemic solution’

On March 27, 2012, Garg sent an email to Alexander, asking to discuss the wait list.

“Four, five, and even six weeks to begin treatment at CAPS is much too long for the students,” Garg wrote. “The length of the wait-time has led to more clinical regression (sometimes to the point of danger), than I can remember since I started working at CAPS in 2003. I think we owe it to our students, both legally and ethically, to find a sustainable, systemic solution.”

In the email, he suggested having the discussion at the next meeting of the Clinical Review Committee. The committee was established after the mass shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007 and was designed to establish protocols for identifying at-risk individuals and to address difficult cases, he said. The committee had not met since the fall of 2010, Garg added.

Garg said no discussion of the waitlist with Alexander ever took place. In a meeting two days later, Garg said, he tried to bring up the waitlist issue, but Alexander focused on his performance.

Early reviews of Garg, as shown by performance evaluations he provided, were glowing. But his 2010 evaluation worsened. Alexander criticized Garg’s collaborative skills, particularly when sharing patients with psychologists. Garg filed comments disputing the evaluation, but said he received no response.

Frustrated with what he saw as CAPS’ unwillingness to address problems, Garg met with then-Vice Provost for Faculty Lynn Lees in early May 2012. He presented her with a list of what he viewed as the main problems at CAPS, among which were the intake system, the increasing wait times and the lack of adherence to standards of care. He set out four proposed solutions, including an external review by an accrediting body and the establishment of an oversight committee.

About two weeks later, he said, Lees sent him an email saying that he should take his concerns back to Alexander. Lees did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Garg sought another meeting on April 3, 2012, about his performance. In that meeting, Alexander and the CAPS training director told Garg that he wouldn’t be allowed to share patients with trainees anymore because of problems collaborating with them, according to Garg’s notes on the meeting. Again, his concerns about the waitlist weren’t discussed, according to the notes.

Garg said Alexander called a third meeting on May 3, 2012, when Garg was read a letter signed by nine CAPS staffers reiterating the concerns they had about his crossing boundaries when sharing patients with a therapist. The letter was attached to his May 29, 2012, evaluation.

Overall, according to the 2012 evaluation, Garg’s performance met “some, but not all, established goals/expectations.” The evaluation again cited collaboration problems.

Garg filed comments disputing the evaluation. But this time, he also filed a formal grievance with Penn’s Division of Human Resources on June 4, 2012. The purpose of the grievance was twofold: to remove the letter from the May 3 meeting from his personnel file and to call for immediate reform of CAPS’ practices.

“I am concerned that the University of Pennsylvania is not always providing appropriate care to our students and I am afraid that there are liability concerns as well,” read the grievance. Garg again recommended an external review and a board of advisers.

Departure from CAPS

On June 14, 2012, Garg was informed that he was being placed on administrative leave for an incident that allegedly happened on June 5, 2012 - the day after he filed his grievance. In September, he was fired.

Garg was accused of possibly violating University policies regarding “work place violence and hostile work environment.” He learned from human resources that a CAPS psychologist had accused him of slapping her thigh during a staff meeting. Garg said it never happened.

“I said, ‘Can I reach out to my patients?’ They said they’d take care of it,” Garg said.

While Alexander would not comment specifically on Garg’s departure, he outlined the procedures for notifying patients when a clinician leaves CAPS. He said all patients are notified and reassigned to other clinicians.

“We do not comment on the reasons for a staff member leaving CAPS,” Alexander said in an email. “But we always offer the client treatment either at CAPS or through a referral, whichever is requested.”

One of Garg’s patients at the time he was placed on leave was a graduate student who had been seeing him since fall 2009. The student, who asked that her name be changed to Zoe in this article for privacy reasons, went to CAPS with severe depression. Zoe enrolled in split treatment, seeing both a therapist and Garg, who prescribed her an antidepressant. Eventually, Zoe just saw Garg.

By June 2012, she saw Garg once or twice a month. She went on a trip for work and emailed Garg upon her return, when she got an out-of-office reply. She figured he was on vacation.

In July, she emailed him again. This time, she didn’t get a reply at all.

“After a certain amount of time, I called the office,” Zoe said. “I called and they were like, ‘I can’t give you any information.’”

Eventually, she got a call back from CAPS. She asked the staffer on the other end of the line where Garg was and asked if it would be possible for someone to write her a refill for her prescription.

“He asked me if I was suicidal. At that point I was not suicidal,” she said. “He gave me no information about Dr. Garg.” When she said that she’d been seeing Garg since 2009, she remembered the staffer saying that it wasn’t CAPS’ policy to have someone see a doctor for that long. He did not encourage Zoe to come in and see someone else, she said.

When Zoe’s prescription ran out, she stopped taking her pills. She slipped back into a severe depression. She called CAPS again on Feb. 5, 2013.

“I could barely get the words out,” Zoe said, crying as she remembered the call. “They made me an appointment for March 17. To me, it was an eternity away. I basically begged - crying - I said I can’t wait.”

Instead of waiting, Zoe went to Student Health Service, where a doctor wrote her a prescription for her antidepressant. Two months later, more stable thanks to her medicine, she emailed Alexander.

“I suffered greatly due to the mismanagement of Dr. Garg’s departure from CAPS,” Zoe wrote in the April 7, 2013, email. “Surely, this cannot have been the first time a practitioner left CAPS. If this was a particularly unusual or difficult situation, then I believe CAPS should have proactively contacted Dr. Garg’s patients to re-establish contact and determine whether further treatment was necessary.”

In an email reply the same day, Alexander apologized for what Zoe had been through.

“This is not the way CAPS works and your email is very distressing,” he wrote. “I agree that you should never have had to go through such an ordeal and I would would like very much to talk with you.” The two set up a time to meet.

At the meeting, Zoe said, Alexander said that there had been a plan to get in touch with Garg’s patients at the time of his departure. He also said CAPS didn’t have Garg’s contact information.

In an email to the DP, Alexander said that in general, CAPS will provide contact information for a former clinician if CAPS has it on file.

Zoe eventually got in touch with Garg, who had established a private practice in Center City aimed specifically to serve college students. She has been seeing him since they reestablished contact.

“I’m OK,” Zoe said of the months spent trying to reconnect with Garg and get back on her medication. “I survived it. But it didn’t have to go that way. They shouldn’t be playing those types of games with people’s lives.”

As Zoe struggled to find him, Garg hired Pennsylvania employment attorney David Dearden to represent him in his dispute with Penn. In late August 2012, the University sent a severance package to Garg through Dearden. If Garg signed the agreement, his employment would have been deemed a voluntary resignation, according to a copy of the agreement provided by Garg.

Garg also would have received a reference letter from Alexander and “a letter recording that an allegation of workplace violence against you was unsubstantiated,” the document reads. The agreement also contained a non-disclosure clause about the terms and circumstances of the severance.

Garg, who still wanted his job at Penn back, decided not to sign the letter. He switched lawyers to Philadelphia employment attorney Nancy Ezold. After he was formally fired from Penn in September 2012, he filed a complaint against the University in mid-October 2012, alleging wrongful termination.

The best outcome, Ezold said, would have been for Garg to get his job back. But that may no longer be possible.

“If that’s not possible, there’s only one other remedy that’s provided in the discrimination laws,” she said. “That’s monetary damages.”

The case is currently pending, awaiting the decision of the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations.

Staff writers Jill Castellano and Alex Zimmermann contributed reporting. Anyone wishing to contribute comments should contact reporter Sarah Smith at smith@thedp.com.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.