With former Penn basketball coach Jack McCloskey at the helm, the Quakers went 87-53 in Ivy competition and won the school’s first Philadelphia Big 5 Championship in 1963. McCloskey left Penn with an overall record of 146-105.

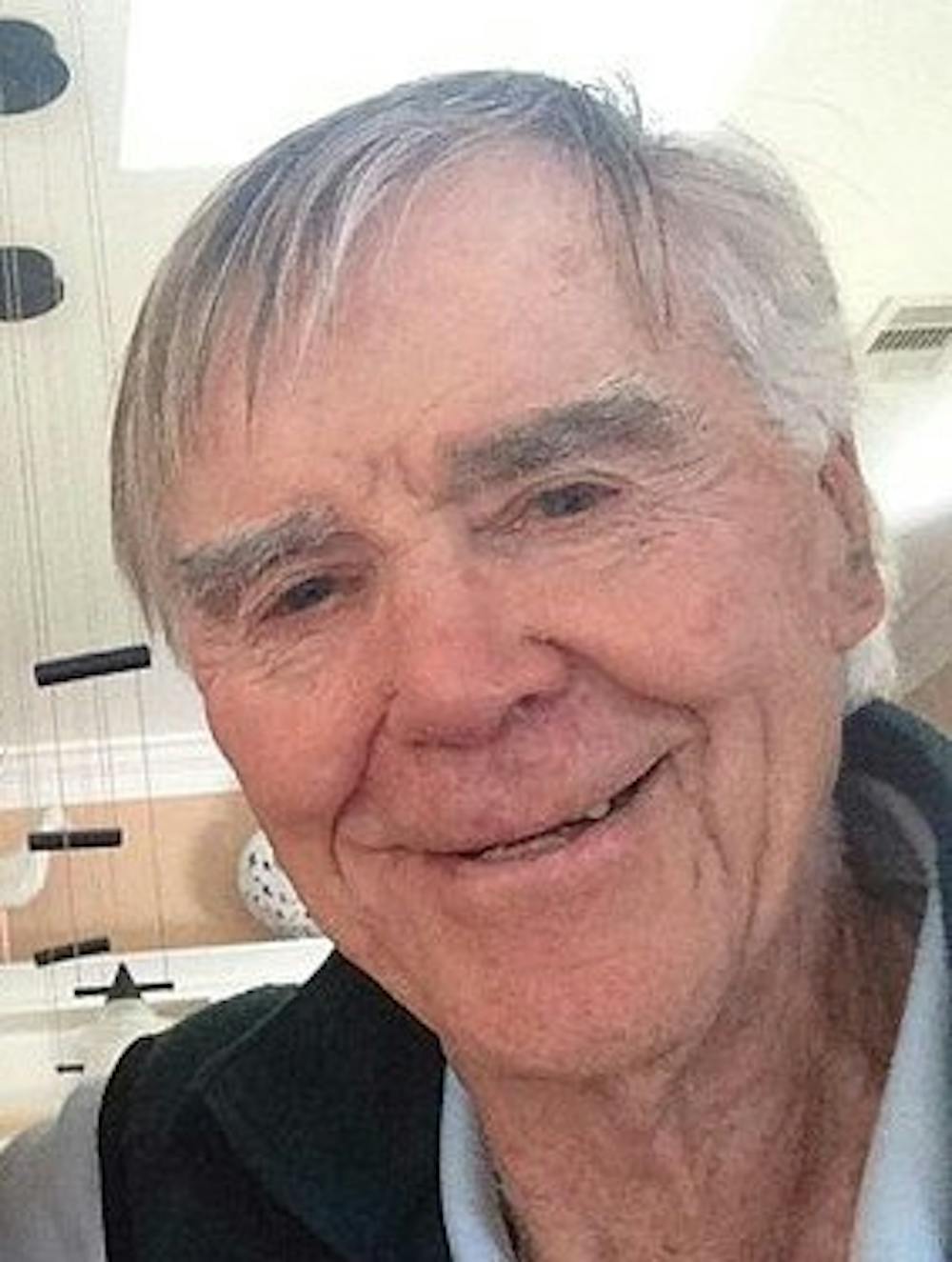

Credit: Courtesy of Creative CommonsJack McCloskey coached Penn basketball during the dawn of the Big 5, from 1956 to 1966. In his 10 seasons coaching the Quakers, McCloskey went 146-105 overall and 87-53 in Ivy League play. McCloskey later coached the Portland Trail Blazers from 1972-74 and was on Jerry West’s Los Angeles Lakers coaching staff in the late 1970s. He is most well-known for his role as the general manager of the Detroit Pistons during the “Bad Boys” era, in which the team won two NBA titles. He has his own banner hanging in the Palace of Auburn Hills.

The Daily Pennsylvanian: First off, can you talk about your undergraduate experience at Penn? Is there anything in particular that you remember most?

Jack McCloskey: As far as my early days there, I came back from World War II, from Okinawa, and kamikazes, and I was very grateful to come back to Penn on my GI Bill. Athletically, prior to that, I was in a program, and played football, basketball and baseball.

DP: You were a Lieutenant in World War II. What was your experience in the military like?

JM: I was in the Navy. I was first on an LST (Landing Ship Tank), and then an LCT (Landing Craft Tank), and I was the executive officer. When we made it to the shore [of Okinawa], the commander went into the interior, and he was killed. So I called up the Flotilla commander to tell him what happened, and I said ‘We’re gonna need somebody,’ and he says ‘We got somebody,’ and I said ‘Oh, who is it?’ and he says, ‘You!’ So at about the age of 20 I was a skipper on an LCT. We were at Okinawa, and later we hit the closest island that was attacked before the bomb, Iejima. It was a very sad situation, because Ernie Pyle, the great writer that went all through Europe, through all those battles, with the Germans, and the Italians, and everything, and he escaped [from those battles]. And then here he comes to this little screwy island [off of Japan], and he gets killed.

DP: Can you talk about your time coaching at Penn? What was it like coaching in the heyday of the Big 5?

JM: I loved coaching at the university. I will tell you, I would have stayed there all my life, if they wanted me. But the director of athletics, Jerry Ford, did something I can never explain. We had a wonderful basketball team [in 1965-66]. We won the Ivy League, and we won the Big 5 Championship. Then this team goes out to the Big Ten,and we win a couple games out there. Now it’s time to get into the NCAAs. So I had a friend, and he tells me who we were supposed to play, and it’s Syracuse. I take a train and go up to see them play.

I get back to Philadelphia, and the assistant athletic director says to me, ‘Jack, you’ve got to talk to [Ford],’ and I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ The NCAA had said that each of the teams that are going to be in [the tournament] need to have a GPA of at least 1.3. But our kids were all great. But this assistant says to me, ‘I don’t think he’s going to sign that paper.’ So I said, ‘All right, I’ll talk to him.’ So I met with him, and I said, ‘Have you signed that paper so that we can play?’ And he said, ‘I’m not going to sign it.’ I said, ‘Why not?’ And he said, ‘[The NCAA] knows that the Ivy League has more than that.’ So I said, ‘Mr. Ford, if you don’t sign it, these wonderful kids are not going to play in this tournament, and they deserve to be there.’

He would not sign that paper. These kids did not play in the NCAAs. And it was a disaster. That’s why I left Penn. There was no way I could associate with that man.

DP: So AD Ford basically thought that Penn was somehow above the baseline NCAA standards and didn’t want to be associated with those types of standards?

JM: He knew that our guys’ [grades] were way above what [the NCAA] was asking for. He

was a pompous Ivy Leaguer that felt like we were above signing a paper like that.

DP: How much did you argue with Ford about signing the document?

JM: I talked and talked, begged and begged, but he just would not do it. He showed the power he had.

DP: What was it like breaking that news to your team?

JM: It was awful. I want to tell you how that team was. Not only were they great basketball players and great scholars, but they were fun to be with.

DP: You coached at plenty of places over your career. How did the Palestra stack up against all the other arenas you visited?

JM: On the collegiate level, I loved coaching at [The Palestra]. That was the epitome for me. I would have stayed [at Penn] forever, except for what I just told you. So I just decided that I couldn’t stay there. And I got couple offers right away. I met with the people from Wake Forest, and I coached there for six years. The first couple years were pretty tough because they didn’t have too many players. Billy Packer was my assistant. He was a great recruiter. He got some players to play, and boy, we were very good the last four years.

DP: Going back to your time at Penn, you got to coach one of the best tandems in Penn basketball history in Stan Pawlak and Jeff Newman. What was it like coaching those two and what so special about the pair in your mind?

JM: First of all, they loved to play. They absolutely loved to be at the University. They gave me their best in every way. As a matter of fact, I’m looking at my wall, and there they are.

DP: While at Penn, you coached alongside one of the great NBA coaches in (then St. Josephs coach) Jack Ramsay, and you guys seemed to be very close. Can you describe that relationship and what it was like competing against one of your good friends?

JM: When we were coaching high school, we used to play up in the Eastern League on weekends to make a few bucks. Jack and I were the closest of friends, not just there, but even when we were competing against each other. We were so close. Our families were so close. The children were close. I talked to Jack yesterday. He’s not in good health. He told me, ‘I think I’ve been told I have a year to live.’ It hurt me so badly, because we were very, very close.

DP: Can you talk about the relationship between the Big 5 coaches during your time at Penn? I understand there was a lot of mutual respect and trust between the coaches.

JM: That was so good. Harry Litwack was at Temple. In my early stages, he talked to me, and he said, ‘Jack, you’ve gotta calm down a little bit. You’ve gotta calm down.’ It was so nice. He wanted to help me, and I always respected him so much. The coach at Villanova, Al Severance, was just a fun guy to be with.

DP: You coached the Blazers in the early ’70s. Can you talk about the adjustment process from coaching the college game to the pro game — what the biggest differences were?

JM: Basically, you should have better talent in the pros. The first couple years when I was in the pros, we had the first pick in the draft. That’s the reason I went [to Portland] instead of going to Philadelphia. So I go in there and I say, ‘Who are you going to take?’ They tell me they’re going to take LaRue Martin. And I said, ‘You know, I’ve been in the college scene for a long time.’ I said, ‘I’ve never heard his name mentioned.’ They said, ‘Well, who would you like?’ Well, I came from the ACC, so I said, ‘Well, I’d like that guy Bob McAdoo. He’s a great player.’ And the general manager at the time said, ‘Well, let’s bring him in.’ So they brought him in, and we went to a hotel meeting. I didn’t go inside, but the owner came, and he wanted to meet McAdoo.

And then the general manager comes out to me and says, ‘Jack, I think you’re gonna get your man.’ So I said, ‘That’s great.’ But about 10 minutes later, the [owner] storms out and he says, ‘This is it. We’re not getting him.’ So we wound up getting LaRue Martin, who is now considered the worst pick in the history of the NBA.

And I got him. Nice young man, but he should not have been picked at that position. It hurt us considerably. We only won a few more games than they did the year before. The second year I was there, midway through the season, we had won more games than we had the entire previous year. The media was coming out and saying how good we were. Then we went on the road and lost our two best players in the back- court. We didn’t do much after that, and I got fired.

DP: Can you try to describe your coaching style? Was your style a competitive one?

JM: There’s no question that I like people who compete. For the teams that I brought to the Pistons, I always selected very competitive people. They were the ‘Bad Boys.’ They were accused of being too tough and too rough. They were wonderful to work with because they did not want to lose.

DP: Going back a little earlier to the 70s, what was it like coaching with Jerry West on the Lakers in the late 70s?

JM: When I got fired by Portland, I didn’t want see another basketball game – I didn’t want to hear another basketball game – for two years. I was really discouraged and broken up. I didn’t think it was fair. My wife said, ‘Jack, you’ve got to put it together. You’ve got to get back to where you were. Why don’t you talk to Jerry West, because he said so many nice things about your coaching, even when you were losing.’ So I called him, and I got on his staff. Jerry’s great.

DP: Why did you decide to become a GM instead of continuing your coaching career?

JM: Well, Dick Vitale recommended me to Detroit, to take over there. He was responsible for that. He was getting fired, and he was such a good guy. He told them about me. So, [the Pistons] said that I could be the general manager, I could be the coach, or I could be both. And being both would be ridiculous. I wanted to be in a spot where I picked the players, and that’s what I did.

DP: You made quite a few trades and acquisitions during your time as Pistons GM. Can you talk about your mindset of always wheeling and dealing, and how important you saw those moves to building a championship contender?

JM: Well, when I was at Pennsylvania, I would put this player in when the game was just about over, and he would play pretty well. And I said to my assistant, “I think we’ve got to give him a little more time.’ And one of the things I did was make a card, and my assistant had to grade him from 1 to 10 on all these different categories, his quickness, his rebounding, his shooting ability, his competitiveness and so forth. I got a score from that, and I said, ‘We’ve gotta play him a little more. He deserves it.’ Well, he played more, and he helped us. I used that card in the NBA. When I scouted guys, I used that same card. It would be dependent on the type of player I was looking at. If I was looking at a guard, the card would have ‘quickness,’ ‘ball handling ability,’ and so forth, and if I’m looking at a big guy, it would say ‘leaping ability,’ ‘defensive ability,’ ‘strength,’ so they were different. Those cards were magic. I used to do it myself. I’d see somebody scout, and they’d be writing down, ‘this guy made a great play in the second quarter, he did so-and-so.’[With the cards], there was no writing. There were numbers. You would just put a number down. And if the number reached 80, he could play in the NBA.

DP: That’s cool that you carried a scouting approach you started at Penn to the pros.

JM: I’ll tell you a funny story. We had two scouts in Detroit, and one was this elderly man that had been at Detroit University for years. When he would scout, he would bring back pages and pages of what he was writing about, and finally, I got him to take up the card. And he was great at that, he made a turnaround. I said, ‘I want you to see the game more.’ And as a matter of fact the other scout we had was Stan Novak, who was a Penn guy, and played for Penn.

DP: Is there any trade or draft story from your years in Detroit that stands out to you?

JM: I can tell you about something we took care of. He is now the assistant to the North Korean guy, Dennis Rodman. Dennis played in a tournament in North Carolina, and all the NBA teams were there. He won the MVP award. A couple weeks passed, and another tournament for all these potential NBA players came about in Hawaii. But he didn’t play well. And I said, ‘Something’s wrong.’ Well, now comes Chicago. It’s the final [tournament], and all the NBA teams were there, and Dennis plays terrible. I had my trainer there, Mike Abdenour. I said, ‘Mike, I want you to go in that locker room, I can’t go in that locker room. You go in that locker room, and see if you can tell me why this guy has disintegrated.’ And he comes out, and he says, ‘Jack, he’s got allergies.’ And I say, ‘Can we repair that?’ And he says, ‘Of course.’ We had the 11th pick at the time, and I liked Dennis very much, but I also liked John Salley. We also had the second pick in the second round. We got it in a trade with Cleveland. I had their pick in the early second round. I said, ‘Do I take the chance on losing a guy who I think could be a great player? Can I be greedy and get two of them?’ I told my scouts Stan Novak and Will Robinson, ‘You get on the phone, and you’re gonna talk to everyone in the league that you know, not scouts, but scouts’ friends. Ask them what’s gonna happen in the draft.’ And I said, ‘Never mention the name ‘Dennis Rodman,’ but tell me if they mention it. I want to know.’ They came back after days and days, and they said, ‘We haven’t heard a word about Dennis Rodman.’ And I said, ‘OK, I’m going to take a calculated risk.’ I took John Salley with the 11th pick, and I got Dennis Rodman with the 27th pick. We got them both. A funny accolade to this is that Dennis is getting his flag rolled up into the rafters at our arena. And I spoke and I told him how great he was. And the first thing he said was, ‘Jack, I was better than John Salley.’

DP: You worked with one of the great NBA coaches in Chuck Daly during your time with the Pistons. Can you talk about what led you to hiring him? I know you guys knew each other from coaching college ball.

JM: I observed his coaching in his Penn years. I knew he knew the game … I knew his mentality, I knew how he did things, and I said, ‘OK, I’m go- ing to invite coach Daly to come up here and meet our people.’ He did, and he did an excellent job the whole time he was here with the Pistons.

DP: With all the moves you made as the GM of the Pistons, was there ever any conflict between you and Daly, or was he always on board with the moves you made?

JM: No, no. I would not interfere with his coaching, because I knew he could coach, and he wasn’t going to interfere with my work. I’ll tell you an interesting story. He came to me one time and he said, ‘Jack, we’ve got some problems with the team.’ I said, ‘OK, what is it?’ He says, ‘I think it’s Adrian Dantley.’ I had traded for Dantley earlier, and Chuck was good with that. We gave up a good young player because we needed an inside scoring player, and that’s how we got Adrian Dantley.

But Daly had come to me and said, ‘Something’s wrong, and Dantley won’t tell me what it is. I want you to talk to him.’ I said, ‘All right.’ So after practice the next day, I take Dantley into the locker room, and we talk. Adrian and I always had a good relationship. But I said to him, ‘Coach thinks there’s problems. I want you to tell me what you think they are.’ And he says, ‘I can’t tell you,’ and I repeated myself, and again he wouldn’t tell me. So I say, ‘Adrian, if you don’t want to talk about it, I’m going to trade you.’ The next day, I flew down to Dallas, and we made a trade. We brought in Mark Aguirre. After the trade, we went 45-5 the rest of the year.

DP: Why did you decide to become a GM instead of continuing your coaching career?

JM: Well, Dick Vitale recommended me to Detroit to take over there. He was responsible for that. He was getting fired, and he was such a good guy.

DP: Wrapping up, do you still follow Penn basketball?

JM: Oh yeah. I follow the football, I follow the basketball as much as I can. I get the football report from the coach and I have it on my computer. I always read it. The first thing I do on a Sunday is see how [Penn] did. I’m still a Pennsylvania man.

DP: Thank you for everything, Mr. McCloskey.

JM: I just want to say that despite what happened at Pennsylvania (in 1966), I loved the University. I loved it. I was so thankful for them allowing a coal miner to come to the Ivy League.

DP: Can I inquire about the coal miner bit?

JM: I’ll tell you the story from the beginning. My dad was a coal miner. In the morning, my mother would bathe him with things from his toes to his knees, and wrap him in paper, and then put rags on him, and then he put his boots on, and it was tough. I was a junior in high school and one breakfast, he says to me, ‘Get your boots. We’re gonna take a ride.’ We have an old junkie car, and we take a ride, and I say, ‘Dad, where are we going?’ And he says, ‘First let me tell you, I’ve talked to your teachers.’ My dad never went to any school. And he says, ‘They’re telling me that you’re not doing what you should. You’re better than what you’re doing. They want you to do better, and I want you to do better. If you don’t, I’m taking you where you will be.’

He took me down in the mines that day. We shut the door up, and you’re going down, and it gets darker and darker. And I said, ‘Heck, I’m gonna be one of the best students this school’s had.’ And I worked like hell to get some decent grades. But my dad is the reason I’ve had any success at all.

SEE ALSO

Q&A with Lafayette coach Fran O’Hanlon

Q&A with Philadelphia Daily News’ Rich Hofmann

Q&A with Penn basketball alum Craig Littlepage

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.