While it is now illegal to use 3-D printers to manufacture firearms without proper licensing, some Penn professors question the significance of that legislation.

In September, Philadelphia became the first city to ban the use of 3-D printers to create part or all of a firearm by anyone other than a licensed gun manufacturer.

The legislation follows debate over 3-D printed guns, which stems from a public computer file released by the Texas company Defense Distributed in May, which could be used to create a firearm called “The Liberator” on a 3-D printer. This November, the manufacturing company Solid Concepts released a video revealing the creation of a metal pistol by a 3-D printer. In the video, the gun could hit a bulls-eye from nearly 100 feet away.

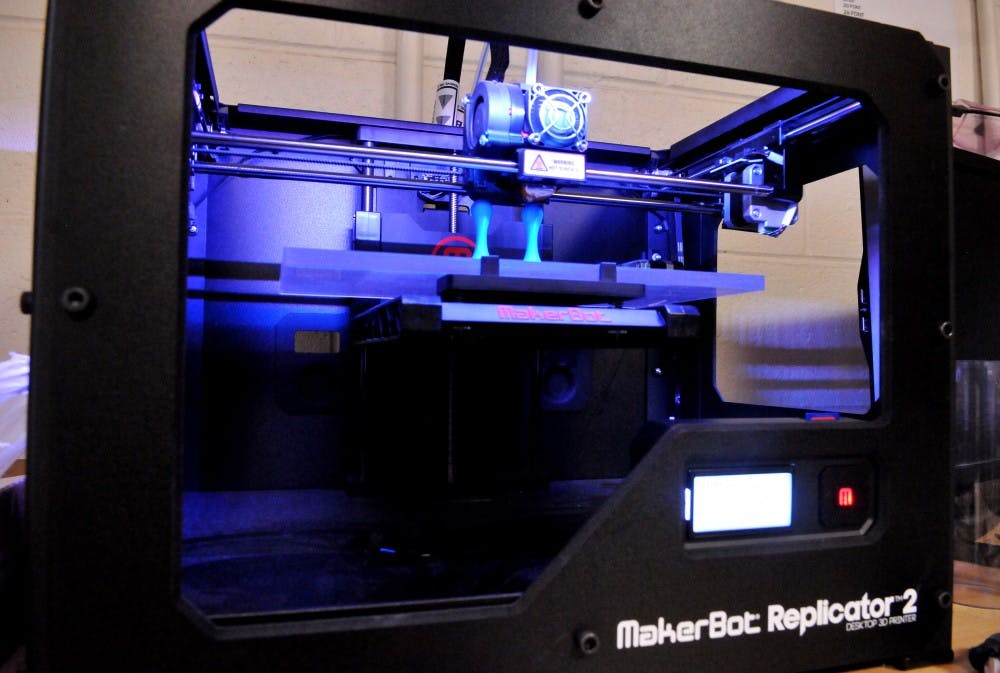

Although there are no known incidences of the creation or use of 3-D-printed firearms in Philadelphia, the issue becomes more pertinent as 3-D printers — devices which both Penn’s School of Engineering and School of Design own — become more accessible and functional.

The metal gun created by Solid Concepts could not be reproduced on any of Penn’s machines even if the blueprint for the design was acquired. Penn’s machines only print in plastic, while more expensive models — often owned by large companies — can vary the materials they use to include various metals.

Related: Bioengineers use 3-D printer to create human organs

However, 3-D-printed plastic guns pose a unique concern, because they would allow people to circumvent the law by carrying weapons unnoticed through metal detectors.

In the normal gun manufacturing world, heavy regulation and oversight by government agencies would make it unlikely for such an undetectable gun to be made. However, the extent to which the government can regulate 3-D printers, like those at Penn, is questionable because materials and information needed for printing are easily available online.

“Trying to outlaw 3-D-printed guns is basically unenforceable,” said Wharton professor David Robertson, who teaches about 3-D printing in his class “Innovation and Production Development.”

“I live in Philadelphia, I have a 3-D printer in my basement, I can download the instructions for printing a gun and I can print it in my basement. It’s extremely unlikely that the police would ever find out about that,” he said. “It was like saying that VCRs could not be used to copy movies from television.”

But even if the law is unenforceable, the practicality of assembling a working plastic firearm from a 3-D printer is uncertain.

“To make something that looks like a gun would be easy,” said Nick Parrotta, a master’s candidate in mechanical engineering and applied mechanics who works in the 3-D-printing lab in Towne. “But you’re probably only creating something that can fire one or two shots. There’s a reason you don’t make guns out of plastic.”

Jonathan Fiene, senior lecturer and director of Laboratory Programs at MEAM, said that he doesn’t think it would be feasible to make a gun with Penn’s machines. The lower temperature models will create friction when the gun is fired, likely resulting in the gun melting or exploding, Fiene explained.

Still, with increased accessibility and the improvement of the technology, the issue remains prevalent.

“The fact that 3-D printing is becoming more advanced and cheaper with easy access means there’s more potential to build something that can give people a capability or tool they shouldn’t have — man, that’s a tough game,” Fiene said.

Now with expiring patents, the price of the machines are expected to go down and accessibility and demand are expected to go up.

The Maker Bot, a small 3-D printer that can be found at Penn, might only cost between $2,100 and $2,700, Parrotta said. Although the higher quality plastic printers at Penn range between 30 and 45 thousand dollars, some 3-D printers already cost under $1,000.

Related: Engineers build ‘titan arm,’ place at competition

However, there is still debate over whether 3-D printing will remain a niche product.

Robertson said that there isn’t a reason for 3-D printing to be readily available in people’s homes.

“If we want a good copy of a photograph — a physical copy — we [can] send it out to one of those companies that’s got a really big expensive machine that we don’t need very often,” Robertson said.

Fiene said the new legislation would probably only be successful if the machines stay centralized over time. Otherwise, it will simply be too difficult to enforce.

Penn faculty also have other concerns related to the legislation.

“The accidental gun violence … that happen[s] within households where a kid gets hold of a parent’s gun and accidentally shoots themselves or a friend wouldn’t happen anymore if you could 3-D print a tailored gun that is fit for an adult but not a kid,” Robertson said.

Under the new Philadelphia legislation, licensed manufacturers still have the authority to use 3-D-printing technology to create firearms, and perhaps custom-made guns like those Robertson describes. Still, Robertson suggests, “we may be heading in the wrong direction with this legislation.”

Stephen Smeltzer, Penn Design’s digital fabrication manager, was more concerned with other legal issues relevant to 3-D technology, like the ability to protect patents. Just as legislation against 3-D-printed guns may be hard to enforce, so would the protection of patented designs.

Parrotta also thinks that focusing on 3-D printing of guns “would somehow harm the technology and limit its usefulness” by overshadowing the benefits of the innovative technology.

Despite controversy over 3-D printing, it is currently used across various fields, encouraging innovation and problem solving.

“It’s an amazing technology,” Evelyn Galban, neurosurgeon and lecturer for the School of Veterinary Medicine, said. Galban has worked with Smeltzer and others from Penn Design to turn CT scans of their animals into 3-D brain models, which can be used to practice surgery techniques.

“We’re just now starting to understand what we can use it for in medicine,” Galban said. “Soon the field is going to open up.”

“The possibilities are endless,” Fiene said. “That’s what makes this such an interesting challenge.”

This article has been updated to reflect that the MakerBot 3D printer costs between $2,100 and $2,700, not between $21,000 and $27,000.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.