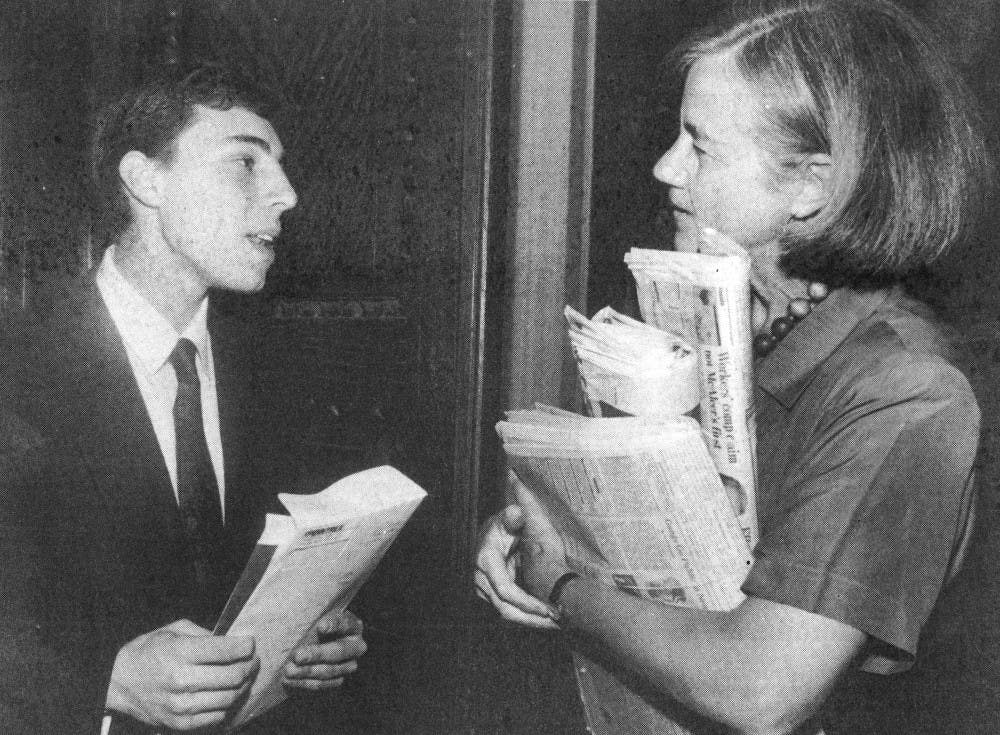

In 1993, a student free speech activist (left) speaks with Lucy Hackney, wife of the late Penn president Sheldon Hackney, at a rally held in the wake of the controversial water buffalo affair.

The spring of 1993 was supposed to be Sheldon Hackney’s swan song — a chance for the departing Penn president to say goodbye to an institution on which he had made a profound and lasting impact during his 12 years in office. Early on in the semester, it had become clear that Hackney was a frontrunner for the National Endowment for the Humanities chairmanship, a nomination that would thrust the southern historian-turned-university administrator onto the national stage.

Instead, Hackney’s final months at Penn became, in his own words, “the spring from hell.”

“I recall it not only as the worst time of my life,” he once wrote, “but as an out-of-body experience.”

For all of Hackney’s achievements over his first 11 years in office, the former president’s handling of two free speech incidents in 1993, his final year, will remain forever etched into his Penn legacy. For some, the incidents — the theft of an entire press run of The Daily Pennsylvanian and the now-infamous “water buffalo” affair — are mere footnotes to Hackney’s time at the University. For others, they are headlines.

The DP theft and the water buffalo affair, both of which had strong racial undercurrents, set off a national debate that brought Penn’s judicial system, the University’s speech policies and Hackney himself under fire.

Related: From water buffalo to BDS, Penn faces free speech questions

By the time Hackney officially left the University to head up the NEH, he had taken a pummeling in the national media that was unlike what any Penn president had ever experienced. U.S. News and World Report started the tradition of giving out an annual “Sheldon Award” — an honor bestowed upon the college administrator who did the most to look the other way while free speech was being stifled on campus. A Wall Street Journal editorial writer who had penned several less-than-flattering pieces about Hackney told the former Penn president that he had been the leading actor in “the darkest moment for human freedom in the history of western civilization.”

The Washington Times dubbed him “Mr. Wimp”; CNN and ABC covered a “Victims of Sheldon Hackney” press conference; scores of other outlets labeled him as the purveyor of political correctness run amok.

Hackney’s handling of the 1993 incidents raised questions that today remain largely unanswered. What role does a university president have in balancing free speech and racial inclusivity on a diverse campus like Penn’s? When is it acceptable for a president to intervene in campus-level judicial proceedings? And in Hackney’s case, is it fair to judge a president — who, by and large, had done much good at his institution — based on actions during his final months in office?

“Sheldon was a man who liked to make people happy,” Linda Wilson, who was Hackney’s chief of staff in 1993, said. Wilson was also a close friend of Hackney’s, who died Sept. 12. “If you put yourself in his position back then, it was impossible to make people happy.”

Related: Remembering Sheldon Hackney

The DP, the buffalo and the ‘fatal flaw’

Hackney’s spring from hell started on the morning of April 15, 1993, when nearly 14,000 copies of the DP — an entire press run — were stolen. A group that called itself the “Black Community” took responsibility for the theft. In a statement on April 15, the group said it had taken the newspapers because of “the blatant and voluntary perpetuation of institutional racism against the black community by the DP.”

In the months leading up to the theft, some black students had grown increasingly frustrated with Gregory Pavlik, a conservative columnist for the DP. In one column, Pavlik angered the black community by questioning the validity of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In another, he claimed that black students were getting special treatment at Penn. At one point, the University’s Judicial Inquiry Office informed Pavlik that he had been accused of 34 counts of racial harassment because of his columns in the DP. All of the charges against him were eventually dropped.

The 1993 theft was not without precedent. In 1987, about 1,000 copies of the newspaper were removed from distribution points in Wharton School buildings. That edition of the DP contained a lead story about a Wharton professor who had been charged with sexually assaulting his step-granddaughter. Wharton administrators said at the time that the story would give “negative impressions” to a group of visiting alumni.

Soon after, Hackney issued a statement in the Penn Almanac condemning the Wharton officials’ actions. That same year, the University published a set of guidelines in the Almanac making clear that the confiscation of campus publications was a violation of Penn’s policies.

In response to the April 1993 theft, Hackney issued a statement in which he attempted to strike a balance between two competing issues. “This is an instance,” he said in the statement, “in which two groups important to the University community, valued members of Penn’s minority community and students exercising their rights to freedom of expression, and two important University values, diversity and open expression, seem to be in conflict.”

Although Hackney went on to say in the statement that he did not condone the theft, DP editors and First Amendment advocates were not pleased with what they thought was a less-than-forceful response. “To us it was a pretty black-and-white issue,” Daniel Gingiss, a 1996 College graduate and former DP managing editor, said, “but President Hackney’s initial response was to sort of argue for the gray in the middle. I think that’s what made a lot of the reporters and editors incredulous at the time.”

Less than two weeks later, national media outlets learned of and began to cover Penn’s water buffalo affair. In January 1993, Eden Jacobowitz, a then-College freshman, had shouted, “Shut up, you water buffalo!” at a group of black sorority sisters who were making noise outside of his high-rise apartment. After the sorority sisters complained to the University, saying that that phrase “water buffalo” was racist, Penn began to pursue racial harassment charges against Jacobowitz.

The brunt of the criticism levied against Hackney during the water buffalo affair came because the then-president did not do anything to intervene in what many viewed as a racially motivated witch hunt against Jacobowitz. “It didn’t help the press to attack someone in the internal judiciary affairs office,” Thomas Childers, a history professor who has taught at Penn since 1976, said. “Sheldon was being nominated for the NEH at the time, and he had a big target on his back.”

The DP theft and the water buffalo affair, though significant, were not Hackney’s only forays into the territory of free speech and racial controversy during his time at Penn. In 1985, then-Wharton lecturer Murray Dolfman referred to a group of black students in his constitutional law class as “ex-slaves.” During the class, he also asked one of the students to stand up and recite the Thirteenth Amendment, the passage of which in 1865 had abolished slavery. Dolfman was eventually suspended for one semester, though Hackney faced criticism for not playing a more active role in the instructor’s discipline.

In 1988, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, known for his anti-white and anti-Semitic views, was invited to speak on campus by several student groups. Farrakhan’s appearance prompted heated discourse among students — not unlike some of the debate surrounding the 2012 Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions conference at Penn — but Hackney stood firm in his belief that Farrakhan deserved an opportunity to speak.

And in 1992, Hackney played a central role in quelling campus riots that sprung up after the Rodney King verdict, a case in which four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted of charges that they had used excessive force while arresting King, a black man.

For Hackney, Wilson said, the goal was always to start a conversation about race-related issues. “He was there to promote conversation, but never to give the final answer,” she said. “That takes time.”

When the national media demanded simplicity from Hackney in the spring of 1993, he responded with complexity; when they demanded clarity, he responded with ambiguity.

“I think the question of hate speech on campus is enormously more complex than the vigilante campaign against political correctness will admit,” Hackney wrote in “The Politics of Presidential Appointment: A Memoir of the Culture War,” a book that focused largely on the DP theft and the water buffalo incident. “I am also aware that, in the public square, complexity is a fatal flaw.”

Related: Penn ranked a top college for free speech

Hackney’s balancing act

Hackney, who grew up in segregated Alabama and became an outspoken civil rights advocate, was keenly aware of the minority student experience at Penn throughout his time in office. It was this, former colleagues and family members say, that largely influenced his response to the incidents in the spring of 1993.

“I think he was torn between trying to promote civility and free speech,” his son, Fain, a 1987 Law School graduate, said. “If you were a student on a college campus, he thought, you should be able to learn without being insulted or yelled at or being made to feel uncomfortable. At the same time, he was always a firm believer in free speech.”

It pained Hackney personally, Wilson said, to learn that some minority students did not feel welcome at Penn.

Hackney, Claire Fagin, a former School of Nursing dean who followed Hackney as interim president for a year, said, was the last president that people would have expected to encounter racial issues while in office. “To me,” she said, “it’s always been ironic that out of all the presidents who have followed, it was Sheldon who had to deal with this.”

Hackney’s problems were compounded that semester because of his nomination for the NEH chairmanship, a position to which he was appointed by former President Bill Clinton. It is possible — even likely, some of his former colleagues say — that both 1993 incidents would have been mere blips on the media’s radar had Hackney not been a national nominee.

“When the black students stole the newspapers,” Childers, the history professor, added, “I think he had a hard time coming down on them. It was his goodness, in that sense — his southern sense of not wanting to be seen as the white southerner who was coming down on black students — that motivated him.”

Related: Under Hackney, a university met a community

In the 1980s, Hackney had been a driving force behind Penn’s passage of a racial harassment speech code, which made it against University policy to “insult or demean” fellow students on the basis of their race or ethnicity. After the water buffalo case settled, the speech code — which Hackney said years later that he regretted — was replaced by a more general student conduct code.

Still, at the time, Hackney maintained ardently that the presence of a speech code did not infringe upon students’ First Amendment rights.

“He felt like he used to in Alabama, in a sense,” Lucy Hackney, Sheldon’s wife of more than 55 years. said. “That bothered him, and he couldn’t just stand by while it happened.”

A blameless president?

Today, those who were involved in Hackney’s final semester at Penn remain divided over how much criticism the former president deserves.

“Those disputes in the last semester of his presidency were, in my view, distractions from the chief business at hand — the academic enterprise,” Mark Frazier Lloyd, director of the University Archives and Records Center, said. “While they were emotional issues and people had very strong feelings about them, they were essentially diverting attention from the underlying mission of the institution.”

Hackney, Childers said, is not blameless in how he handled both incidents, but he believes that others — particularly Penn’s judicial system — are much more guilty. “I don’t think Sheldon disgraced himself at all,” Childers said. “I think the University did.”

Others say that Hackney is far from innocent. “You have to be a rank hypocrite to praise Sheldon Hackney for his time at Penn when he left in the wake of such damage to academic culture and free speech,” Harvey Silverglate said. Silverglate is a co-founder of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a free speech advocacy group that was born largely out of the water buffalo affair. Alan Kors, a Penn history professor who co-founded FIRE with Silverglate, defended Jacobowitz in 1993.

Hackney’s insistence throughout the spring of 1993 that he could not intervene in the water buffalo case, Silverglate said, remains “the greatest excuse for a cop out that one can imagine. Sheldon Hackney may not have invented the cop out, but he perfected it to an art.”

The water buffalo affair prompted questions through higher education about how much power college presidents should have to get involved with judicial proceedings against individual students — especially when those proceedings draw national attention. Although Hackney later said in his NEH Senate confirmation hearings that he would have ideally had more personal control in the water buffalo affair, he made it clear that Penn’s president and provost did not have a role in the University’s judicial process.

“With regard to disciplinary cases, I was similar to a mayor, who cannot tell the district attorney what to do, and I was not at all like the chief executive officer of a corporation, who can tell anyone in the organization what to do,” Hackney wrote in his book. “That a college president does not have the power of an army general is a bit of ‘context’ that my journalistic stalkers neglected to pass along to their readers.”

Lasting impacts

The DP theft and the water buffalo affair both left lasting impacts — on Hackney, on Penn and on higher education.

“He understood why people could disagree with the way that it was handled, but the attacks against him became so personal,” Fain Hackney said. “He never understood that. He always thought that if he could sit down with people and explain, they’d at least see where he was coming from.”

The 1993 incidents also led to noticeable changes in Penn’s culture. Throughout the 1990s, Wilson said, race relations on campus improved steadily. The DP theft also made the newspaper staff itself more race conscious, said Gingiss, the former managing editor. In the fall semester of 1993, for example, the DP published a joint series on race relations with “The Vision,” a black student publication. It marked the first time that the DP had collaborated with another campus publication on a project.

“We were getting letters from alumni who said they’d never give us another nickel because of what happened,” Fagin said of her interim presidency, which lasted through mid-1994. “Things came a long way after Sheldon’s last semester.”

Lloyd, the University Archives director, noted that later administrations have been more hands on than Hackney was in dealing with damage control for campus controversies that draw the eye of the national media. “Generally speaking, Sheldon would not intervene,” Lloyd said. “He was not heavy handed. He would not impose his authority through arm twisting around campus.”

Lloyd cited the 2005 “Ivy League grind” case — in which the Office of Student Conduct pursued charges against an Engineering junior who had posted photographs of a couple having sex near a high-rise window — as an example of the different styles of later administrations. In that case, the University dropped its charges against the student soon after the story began to pick up steam.

The 1993 cases, Childers added, created a sense among some at the University that they could no longer trust the inner-workings of Penn. “The University did not cover itself in glory back then, and it deserved a very rough treatment from the press,” he said.

The DP theft and the water buffalo affair both ended somewhat abruptly. In the DP case, the University dropped its charges against the students who had taken the newspapers, saying that the incident had been a learning experience for everyone. In the water buffalo affair, the black sorority sisters ultimately withdrew their complaint against Jacobowitz.

Although Hackney developed a deep mistrust toward some in the national media following both cases, he never turned his back on the DP, Charles Ornstein, a 1996 College graduate and former DP executive editor, said. In 2009, for example, Hackney attended the DP’s 125th anniversary celebration, taking the time to speak with staff members and poke fun at his role in the 1993 theft.

Years earlier, in 1984, Hackney had played a central role when the DP severed its financial ties with the University, becoming an independent corporation. Reporters at the newspaper saw Hackney on the whole as an accessible and down-to-earth president, Ornstein said.

“In the interest of bending over backwards for good race relations on campus, the administration clearly took steps that were over the top,” Ornstein, who once took a history seminar with Hackney, said. “But the fact that President Hackney was willing to come back [to the DP celebration] was a testament to how much he respected the overall work of the DP, and to the sort of person he was.”

Although Hackney largely failed to turn the spring of 1993 into a teachable moment — which had been his ultimate goal, Wilson said — he found a way to move on from the experience and return to Penn several years later, as a faculty member in the history department.

“I don’t think Sheldon would have claimed any credit for the improvements in race relations that occurred in the years after he left,” Wilson said, “but he would have been proud to see it.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.