A group of bioengineers at Penn is one step closer toward the creation of full-fledged human organs in the laboratory.

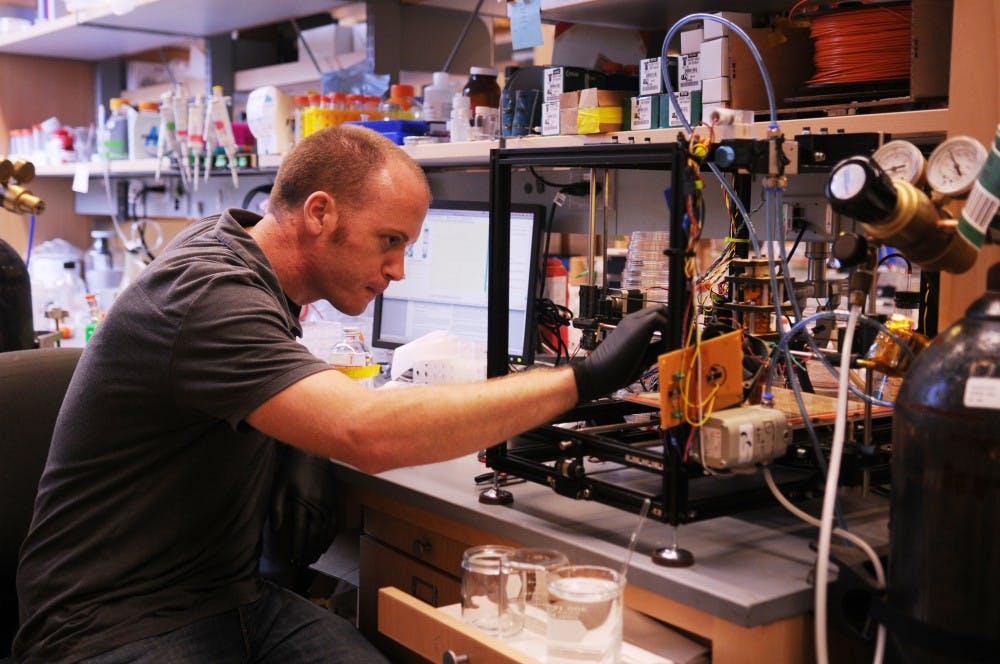

Through the use of open-source 3-D printers, researchers at the Tissue Microfabrication Lab have come up with a cheap and innovative way to create a model of an effective blood vessel network, which is vital to the survival of any organ.

The project is a joint collaboration between Penn and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is being led by School of Engineering and Applied Science professor Christopher Chen.

Chen — whose team is funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Penn Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the Center for Engineering Cells and Regeneration — is also working closely with postdoctoral fellow Jordan Miller and MIT professor Sangeeta Bhatia.

Miller explained that the main motivation for this project was to come up with a safe, economical and readily available way to treat patients who are in dire need of organ transplants.

“There are 100,000 patients on the organ transplant waiting list in the U.S. alone, and sadly, thousands die annually waiting for donor organs which could have saved their lives,” Miller said.

“Bioengineers across the world are trying to develop cell-based therapeutic solutions which work better than implants as cells outperform devices,” he added. “But the problem lies with fragile organs like the liver, which are not so easy to recreate in the lab.”

Even techniques like bioprinting — which involves the layer by layer buildup of cells into complex 3-D structures to form organs and organ tissues — are rendered ineffective by the complicated 3-D blood vessel networks that, until now, have been impossible to recreate in the lab.

Penn and MIT’s research aims to alter that.

Partially inspired by the “lost-wax casting” method used to create bronze sculptures , the process of creating blood vessel networks consists of a number of steps.

First, Chen’s team creates a model of the vessel using a computer. Then, using an open-source 3-D printer, the team prints a mold of the model using molten sugar.

Once the sugar hardens, the mold becomes solidified and structured.

Organ tissue cells created in the lab and stored in a gel are then poured over this. After the gel solidifies, the sugar is dissolved to complete the process, which yields a complete organ tissue that is durable and can be easily shipped to any lab across the globe.

The whole process is quick and inexpensive, allowing the researchers to minimize the time it takes between creating a computer simulation and producing a physical model.

Chen’s team is optimistic about the direction of the project and the collaborative nature of the research.

“As we have come to appreciate the scope of the grand challenges that lie ahead, the entire research community has become much more collaborative,” Chen said in an email. “And the internet has eliminated many of the barriers associated with long-distance collaboration, allowing us to form teams with the best researchers in our field.”

Chen and Miller both agreed that, while their research marks an important milestone in the field of regenerative medicine, there remains much work to be done before the goal of having laboratory-created organs ready for transplants becomes a reality.

“It will probably take 10-15 years for the technologies to advance sufficiently for reproducible production of large-scale tissues, and another 10 years for initial clinical trials to test safety and efficacy of such tissues for medical use,” Chen said.

He added that, although it may sound like a long time, a new drug in the pharmaceutical industry might take 10-20 years on average to become approved for therapeutic use.

Miller agreed that this will be a more long-term process.

“The future is bright as we may expect one day to be able to take a patient’s cells, create the organs needed by him in the lab and transplant it back into his body,” he said.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.