As college students around the nation apply for Teach for America, some debate the true effectiveness of the program.

Since its founding in 1990, TFA has won itself a prestigious reputation.

Its name recognition and philanthropic cause — sending future leaders into disadvantaged K-12 schools throughout America — has made it a very popular job choice among college graduates and is often compared to getting into a revered graduate program.

The program, whose final deadline for the 2012 teaching corps is today, received 48,000 applications last year. However, only 14 percent of applicants were accepted.

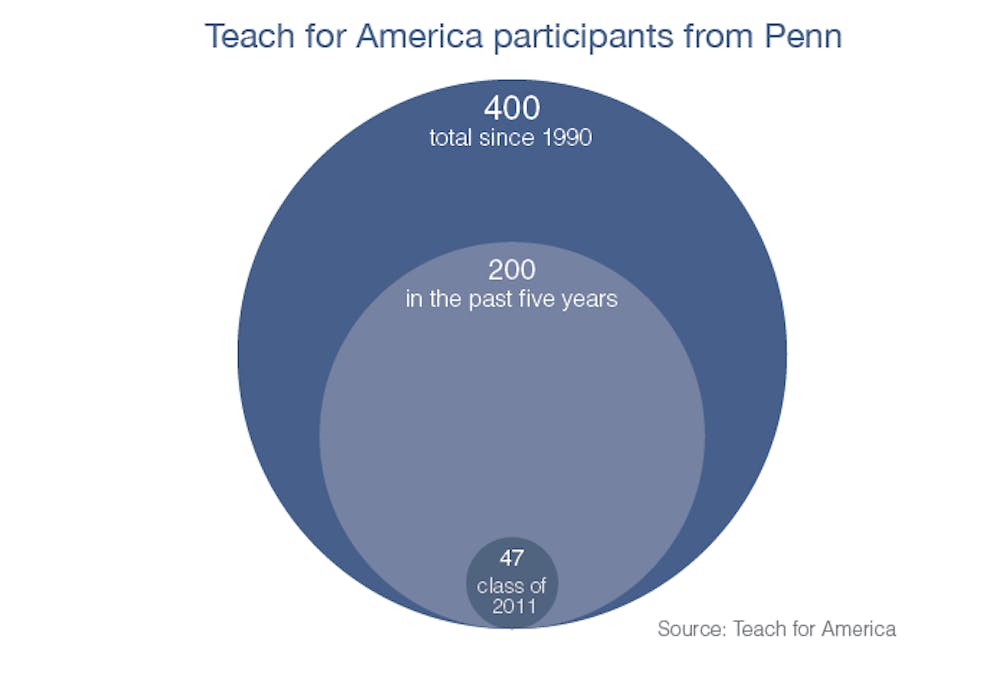

Over the past 21 years, 400 Penn graduates have entered their corps, including 47 from the class of 2011, according to TFA.

According to Penn’s Career Services, it is the top employer of graduating seniors.

However, members of the Penn community are weighing the pros and cons of the two-year program.

Choosing TFA

For many, the decision to become a TFA corps member is an important one.

TFA teachers have the lives of impressionable children and teenagers in their hands, working with disadvantaged students in some of the poorest schools in the nation.

For some, love for teaching and social justice propels them to join the program, while others are perceived to join TFA as a stepping-stone to a graduate program or another career.

Director of the TFA program at Penn’s Graduate School of Education Mary Delsavio said TFA teachers have a “passion for education. They are very interested in making sure students achieve.”

Eleanor Fulbeck, former TFA corps member and GSE post-doctoral fellow, said she applied to TFA “because of the prestige of the program … [and her] broad interest in social justice.”

Several years later, she is out of the classroom but still dedicated to education.

“For some people it probably is a resume builder, but for others it is not,” she said. “There are easier ways to build a resume.”

College senior and 2012 corps member, Mimi Owusu, said TFA is “definitely valued” by employers, but it is also “a very big sacrifice.”

TFA teachers are “doing one of the hardest jobs they will ever do,” she added.

When Owusu tells other Penn students that she is going to become a TFA teacher, she said their initial response is to congratulate her because they know how prestigious the program is. “And then there is [their] afterthought, like ‘wow that is going to be tough.’”

High turnover rates

TFA has received both praise and criticism for its approach to education. It is mostly criticized for not aiding the problem of teacher retention.

Krista Cortes, GSE graduate student, does not support the program. She said teacher retention is a large problem in disadvantaged schools, and TFA’s minimal time commitment of two years only adds to that problem.

“There is research out there that shows that teachers get to their best in their third to fifth year [of teaching].”

She added that one of TFA’s appeals is its short time commitment. She believes that if a teacher is willing to stay in the classroom for five years or more, they might as well get a graduate degree in education and become a teacher.

“I wouldn’t be opposed to them completely getting rid of the program,” Cortes said. She added that most TFA teachers are not appropriately prepared to take responsibility for the education of their pupils.

The majority of TFA graduates “don’t stay in the classroom,” Fulbeck said. She believes this is a huge financial cost for school districts because of high turnover rates and a “morality” cost for students who lose “familiar faces” once their teachers leave.

Fulbeck compares TFA to a “band aid,” temporarily helping a larger problem. However, she said having a teacher at a given school for two years is better than having long-term substitutes in classrooms or combining classes.

College senior and 2012 corps member George Hardy said the relations built between TFA teachers and students “doesn’t have to stop after two years.” He said his decision to stay after his two-year TFA commitment will depend on the “politics behind the job” in the Detroit school district where he will be teaching. He added it has nothing to do with his love for teaching.

While many agree teacher retention is a problem, some believe TFA employs a strategy of recruiting people who have other ambitions.

“The biggest pro of TFA is that it gets people involved in education that might otherwise go into another sector,” Fulbeck said.

Owusu said TFA recognizes that many of their teachers plan on going into business and politics. With an insight into the problems that some school districts face, they will be more likely to create better, school friendly policies if they are in a position to do so, she said.

Delsavio, who was a 2002 corps member, “left the classroom, but I haven’t left education. I haven’t left this program.”

Minority representation

According to the TFA website, the program strives to recruit a diverse corps to have a larger impact on the students.

The 2011 corps was 65 percent caucasian, and the rest were minorities such as African American, Latino and Asian American.

Hardy believes it is important for TFA to put more minority teachers into classrooms, because this will benefit minority students. However, “recruitment strategies are not the best for minorities,” he said.

He believes that minorities are not well-represented in part because some are not in a financial position to turn down higher-paying jobs.

Compensation for participants ranges from $30,000 to $51,000 per year.

Despite criticism of the program, GSE associate professor Laura Desimone still believes it is “a terrific way to get a lot of talented people into schools who would never otherwise be there.”

Placing “smart, motivated people in the classroom doesn’t seem like a bad thing to me.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.