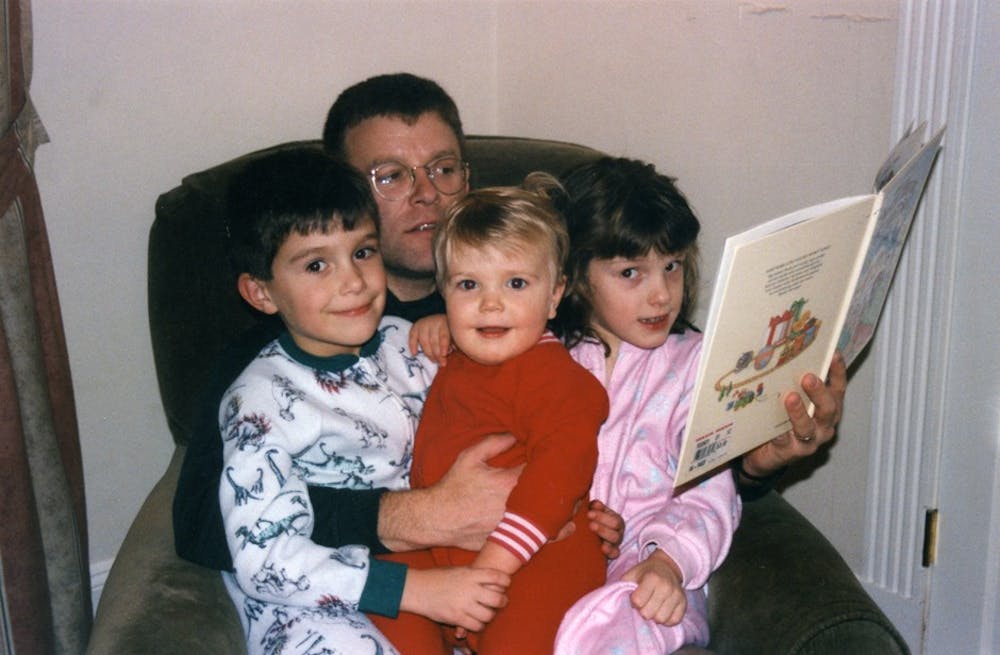

Mark Charette, who was in a meeting in the north tower on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, spent Christmas Eve 2000 with his three children, Andrew, Jonathan and Lauren. Charette and his wife, Cheryl Desmarais, met at Penn and both graduated from the Wharton School in 1985. (Courtesy of Cheryl Desmarais)

On any given day, hundreds of Penn students may pass it by while giving little or no notice.

But tucked away in front of Van Pelt Library it has sat since the second anniversary of 9/11 — a plaque paying homage to 16 alumni who were killed in the attacks.

The plaque, though simple and nondescript, opens the door to a lifetime of stories. The story of an insurance broker and an environmental worker. The story of a son or daughter, a father or mother, a brother or sister. The story of a Penn Quaker. The story of an American.

In this special feature, we take a look at five of those stories, through the eyes of those who knew them best.

A Father, a Coach and a Friend

In May 2001, Jill Abbott brought her father the news he’d been waiting patiently throughout her 11-year marriage to hear: he was going to be a grandfather.

Abbott wouldn’t know it until months later, but the news was so moving that her father, 1967 Wharton graduate Michael San Phillip, was brought to tears, having to excuse himself to a nearby room.

But San Phillip — the vice president at Sandler O’Neill & Partners, located on the 104th floor of the south tower — would never have the opportunity to meet his granddaughter.

San Phillip was killed when United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the tower. He was 55.

Abbott gave birth nearly four months after the 9/11 attacks. She and her husband named their daughter Michele, after San Phillip.

“He was probably the most generous person I’ve ever known, someone who would do just about anything to help out,” Abbott said. “He was my dad, he was my tennis coach and he was my friend.”

Abbott added that family and friends have often called her “a female version of my father. We were definitely cut from the same cloth.”

In addition to their love for tennis, Abbott and San Phillip shared a bond that both would cherish together until that fateful September day — a connection to Penn.

“My dad always spoke fondly about his time there,” said Abbott, who earned her master’s degree from Penn’s Fels Institute of Government 26 years after her father finished his undergraduate work, in 1993.

San Phillip’s wife, Lynne, gave birth to Abbott while her husband was finishing up his senior year at Penn.

Abbott said she remembers her parents telling her stories of how they would take her in a stroller to Smokey Joe’s so they could spend time with friends from college.

“Just the fact that I was able to share that Penn legacy with him means the world,” she said.

San Phillip’s Penn story, however, doesn’t end with his death.

Upon hearing that his former classmate and lacrosse teammate had been a 9/11 victim, 1967 College graduate Howard Freedlander felt he needed to act. After getting permission from San Phillip’s family, Freedlander contacted the University about the prospect of setting up a scholarship in memory of his old friend.

Several months and a few hundred thousand dollars later, Freedlander helped launch the Michael San Phillip Memorial Scholarship.

Since it was first awarded in the 2002-03 academic year, the scholarship has provided support to eight scholar-athletes at Penn. To date, the Class of 1967 has helped raise more than $500,000 for the Michael San Phillip Memorial Scholarship.

Though Freedlander lost touch with San Phillip over the years, he said his work with the scholarship has provided a better sense of what type of man he was.

“I was dumbfounded that a tragedy which had touched so many families and so many people had touched someone I knew and liked,” Freedlander said. “This was my way of giving back.”

A Family Man

Mark Charette left his Millburn, N.J., home early the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, promising his wife he’d be back in time to take their children to karate class later that evening.

Hours later, Cheryl Desmarais, Charette’s wife, listened in disbelief to the initial radio reports of the attacks on the twin towers.

Desmarais immediately picked up the phone, hoping that her husband had gone to the Midtown Manhattan offices of Marsh & McLennan, the insurance brokerage firm where he worked.

When she finally managed to reach his voicemail, despair filled her heart.

Charette was scheduled to be in a day-long meeting on the 100th floor of the north tower, the answering machine said.

As Desmarais put down the phone receiver, the words rang somberly in her mind.

“I knew right then that he wouldn’t have left the building because of the kind of person he was,” she said. “He’d be stopping to help people, stopping to make sure everybody was able to get out.”

Desmarais would spend the next few days waiting for a phone call that never came.

Though she rarely speaks openly about the day she lost her husband, thinking back on her time with Charette brings up nothing but smiles.

Desmarais and Charette met as undergraduates at Penn, both initially studying at the Engineering School and eventually transferring into the Wharton School. After struggling in one of her classes during sophomore year, she began sitting next to Charette because “he seemed like a nice, smart guy who might help me out.”

A few months later, Charette asked her out on their first date. They became engaged after senior year finals, both graduating from Wharton in 1985.

“Penn was very near and dear to our hearts,” she said. “I have a lot of happy memories of Mark from our time there.”

After 9/11, Desmarais said the University reached out to her to confirm her husband’s death, as well as to interview her for a tribute article.

John Zeller, vice president for development and alumni relations, said his office fielded hundreds of inquiries from alumni in the days following the attacks.

In addition to breaking usual protocol by providing personal contact information to those who requested it, the University set up multiple online message boards to track the whereabouts of alumni who were known to work in the New York or Washington area, he added.

While Desmarais had some brief contact with Penn after 9/11, it wasn’t until last year — her 25th college reunion — that she made the trip back to campus for the first time since the tragedy.

Looking to the future, she is hoping another new Quaker may soon be on the way.

Her oldest son, Andrew — one of three of Charette and Desmarais’ children — has already expressed a strong interest in attending Penn in two years, she said. He is currently a junior in high school.

“The kids adored him; his family was the most important thing in his life,” she said. “I want my kids to remember who their father was. He didn’t leave us. He would never leave us.”

One Final Letter

A few days after Nicholas Humber — a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11, which crashed into the World Trade Center’s north tower — was killed, his son, Jordan, decided to take a look through his father’s old bedside cabinet.

While rummaging through the drawers, he came across an envelope that had his name written on it. Opening the envelope, Humber held up a three-page letter contained inside and began to read.

“My dad had written a note about how proud he was of the man I’d become, how happy he was to see what I was doing,” he recalled.

The letter was dated Sept. 10, 2001.

“That [date] was just eerie to see,” Humber said. “It’s almost like he knew something was going to happen.”

While Humber said his father — who received his masters degree from Wharton in 1967 — never spoke with him about his time at Penn, he remembers him as a man who was always hungry for knowledge.

Nicholas joined the Environmental Protection Agency in 1971, shortly after it was founded. Throughout his career, he was often at the forefront of new engineering technologies and theories.

When his father’s flight — which had been on route to Los Angeles from Boston — crashed into the tower, Humber was “many miles and many worlds” away from the tragedy that was unfolding in New York, he said.

Just 19 years old at the time, he was on a group hiking and camping trip in the wilderness of Wyoming. Though his group had virtually no means of communication, Humber said he began to think something was wrong when he was unable to spot a single airplane in the pitch black night sky on Sept. 11.

When he was soon told by a group leader what had happened, the news came as a complete shock. Humber had never even known that his father was planning on flying while he was away in Wyoming.

“Having to come out of the wilderness and back into the real world, you have to learn how to walk upside down,” he said. “That’s what it was like for me.”

Since the aftermath of 9/11, Humber said he has adjusted to normal life. Though he has many happy memories of his father, he admittedly tries to avoid associating with public events commemorating the anniversary of the tragedy.

“Things like that are for the public, not us,” he said. “We remember my dad silently for what he was — a great guy.”

The American Dream

When she was 42, Tu-Anh Pham gave birth to her first daughter. After a six-week maternity leave, she returned to work at Fred Alger Management, located on the 93rd floor of the north tower.

The date was Sept. 10, 2001.That week, Pham had been “anxious and enthusiastic to go back,” her husband Thomas Knobel recalled. “She was doing important work.”

Hours after she left home the morning of Sept. 11, she became one of 35 of the firm’s 39 employees to die in the attacks.

In her early years, Pham would not have been a likely candidate for a position at the center of New York’s financial world. She arrived in the United States when she was 15, after she and her family were airlifted out of South Vietnam in 1975 because of the war.

Despite knowing no English when she came to the country, she graduated from high school with high honors.

Looking back, Knobel said he remembers his wife as having a “very entrepreneurial spirit” and being “highly analytical.”

It was that drive and determination that landed Pham a spot in Wharton’s MBA program in 1987.

Going to Wharton “helped her career dramatically,” Knobel said. “It opened so many doors for her and widened her perspective,” he explained, adding that he has kept in touch with many of her friends from business school.

Twelve years after his wife graduated from Wharton, Knobel watched on television as the twin towers crumbled to the ground.

“We lived in Princeton at the time,” Knobel recalled. “But I moved back to my hometown in upstate New York [after the attacks]. Part of the reason was to avoid a lot of the emotion that was flowing in New York and New Jersey.”

In the years that followed, his family in upstate New York helped him raise his 6-week-old daughter, Vivienne Hoang-Anh Knobel.

Fast-forward to today, Vivienne is starting fifth grade.

“She is a top student in her class,” Knobel said. “She has intelligence and mathematical skills that she inherited from her mother.”

Although Knobel has explained to his young daughter what happened to her mother, he feels it is important to “keep the kids away from the geopolitical aspect of Sept. 11.”

“It’s easy to become obsessed with the implications, the religious conflicts, the wars that we’ve fought since,” he said, but, for his daughter, “it’s just important for her to grow up knowing about her mother.”

A Bond of Brotherhood

On Sept. 10, 2001, Mukul Agarwala walked into the 94th-floor office of Fiduciary Trust International, located in the south tower.

It was his first day at a new job.

The following day, Agarwala became one of nearly 3,000 victims of the 9/11 attacks.

While Agarwala began his second day at work on the morning of Sept. 11, the rest of his family was at a funeral, paying their respects to a lost cousin. Agarwala’s three brothers had asked if he would be able to take off the morning to attend with them, but he felt that his second day on the job was too soon to ask for the day off.

“It’s incredible to think that one decision like that made such a huge difference,” said 1989 College graduate Ajay Agarwala, one of Mukul’s two younger brothers.

While Ajay was attending Penn as an undergraduate in the late 1980s, Mukul joined him on campus, taking graduate courses in Wharton and living nearby in Philadelphia. Mukul completed his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering from Penn in 1984 and his master’s degree in 1990.

Ajay said Mukul’s time at Penn “was one of the happiest periods in his life. I know he truly enjoyed it there.”

Ajay and Mukul would see each other often during their years on campus. They even lived together for a few months in 1989.

The second oldest of the four brothers, Mukul “was always the glue that held our household together,” Ajay recalled. “If any of the four of us were in separate places, he’d be the one calling, planning trips, keeping us in touch.”

Sanjay Agarwala, the third of the four brothers, remembered Mukul as “a true big brother I could always look up to.”

While both Ajay and Sanjay spent time with their older brother in different capacities, they always agreed on one thing — Mukul was among the most generous men they’d ever known.

After the attacks, Sanjay learned through a co-worker of Mukul’s that his brother had been spotted walking up and down flights of stairs in the building, trying to help as many people to safety as he could.

“He was just the type of person that, if you needed help, he was going to help you,” Sanjay said. “That’s how we’ll always remember him.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.

Read more in the series »

Read more in the series »